|

|

| (11 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) |

| Line 1: |

Line 1: |

| − | The '''Qur’ān''' '''القرآن''' }};''{{al-ķur'ān}}'', literally "the recitation"; also sometimes [[Arabic transliteration|transliterated]] as '''Quran''', '''Koran''', or '''Al-Qur'an''') is the central [[religious text]] of [[Islam]]. Muslims believe the Qur'an to be the book of divine guidance and direction for mankind and consider the text in its original [[Arabic]] to be the literal word of [[God]], [http://www.usc.edu/dept/MSA/quran/002.qmt.html#002.023 Qur'ān, Chapter 2, Verses 23-24 revealed to [[Muhammad]] over a period of twenty-three years ''Living Religions: An Encyclopaedia of the World's Faiths,'' Mary Pat Fisher, 1997, page 338, I.B. Tauris Publishers, [http://www.usc.edu/dept/MSA/quran/017.qmt.html#017.106 Qur'an, Chapter 17, Verse 106] and view the Qur'an as God's final revelation to humanity [http://www.usc.edu/dept/MSA/quran/033.qmt.html#033.040 Qur'an, Chapter 33, Verse 40] Watton, Victor, (1993), ''A student's approach to world religions:Islam'', Hodder & Stoughton, pg 1. ISBN 0-340-58795-4

| + | [[File:lighterstill.jpg]][[File:Koranmcmastersingle.jpg|right|frame]] |

| | | | |

| − | Muslims regard the Qur'ān as the culmination of a series of divine messages that started with those revealed to [[Adam]] — regarded, in Islam, as the first [[prophet]] — and including the [[Suhuf-i-Ibrahim]] (''Scrolls of [[Abraham]]''),<ref>[http://www.usc.edu/dept/MSA/quran/087.qmt.html#087.018 Qur'ān Chapter 87, Verses 18-19]</ref> the [[Tawrat]] ([[Torah]]),<ref>[http://www.usc.edu/dept/MSA/quran/003.qmt.html#003.003 Qur'ān, Chapter 3, Verse 3]</ref><ref>[http://www.usc.edu/dept/MSA/quran/005.qmt.html#005.044 Qur'ān, Chapter 5, Verse 44]</ref> the [[Zabur]] ([[Psalms]]),<ref>[http://www.usc.edu/dept/MSA/quran/004.qmt.html#004.163 Qur'ān, Chapter 4, Verse 163]</ref><ref>[http://www.usc.edu/dept/MSA/quran/017.qmt.html#017.055 Qur'ān, Chapter 17, Verse 55]</ref> and the [[Injil]] ([[Gospel]]).<ref>[http://www.usc.edu/dept/MSA/quran/005.qmt.html#005.046 Qur'ān, Chapter 5, Verse 46]</ref><ref>[http://www.usc.edu/dept/MSA/quran/005.qmt.html#005.110 Qur'ān, Chapter 5, Verse 110]</ref><ref>[http://www.usc.edu/dept/MSA/quran/057.qmt.html#057.027 Qur'ān, Chapter 57, Verse 27]</ref> The aforementioned books are recognized in the Qur'ān,<ref>[http://www.usc.edu/dept/MSA/quran/003.qmt.html#003.084 Qur'ān, Chapter 3, Verse 84]</ref><ref>[http://www.usc.edu/dept/MSA/quran/004.qmt.html#004.136 Quran, Chapter 4, Verse 136]</ref> and the Qur'anic text assumes familiarity<ref>"The Qur'an assumes the reader to be familiar with the traditions of the ancestors since the age of the Patriarchs, not necessarily in the version of the "Children of Israel" as described in the Bible but also in the version of the "Children of Ismail" as it was alive orally, though interspersed with polytheist elements, at the time of Muhammad. The term Jahiliya (ignorance) used for the pre-Islamic time does not mean that the Arabs were not familiar with their traditional roots but that their knowledge of ethical and spiritual values had been lost." ''Exegesis of Bible and Qur'an'', H. Krausen. http://www.geocities.com/athens/thebes/8206/hkrausen/exegesis.htm </ref> with many events from Jewish and Christian scriptures, retelling some of these events in distinctive ways, and referring obliquely to others. It rarely offers detailed accounts of historical events; the Qur'an's emphasis is typically on the moral significance of an event, rather than its narrative sequence. Details to historical events are contained within the [[Hadith]] of Muhammad and the narrations of Muhammad's Companions ([[Sahabah]]).

| |

| | | | |

| − | The Qur'anic text itself proclaims a divine protection of its message: ''Surely We have revealed the Reminder and We will most surely be its guardian.''<ref>[http://www.usc.edu/dept/MSA/quran/015.qmt.html#015.009 Qur'ān, Chapter 15, Verse 9]</ref><ref>[http://www.usc.edu/dept/MSA/quran/005.qmt.html#005.046 Qur'ān Chapter 5, Verse 46]</ref>

| + | '''The Qur’an'''[1] (Arabic: القرآن al-qur’ān, literally “the recitation”; also sometimes transliterated as Quran, Qur’ān, Koran, Alcoran or Al-Qur’ān) is the central religious [[text]] of [[Islam]]. Muslims believe the Qur’an to be the [[book]] of [[divine]] [[guidance]] and direction for mankind, and consider the original Arabic text to be the final [[revelation]] of [[God]].[2][3][4][5] |

| | | | |

| − | The Qur'anic verses were originally memorized by Muhammad's companions as Muhammad recited them, with some being written down by one or more companions on whatever was at hand, from stones to pieces of bark. In the [[Sunni]] tradition, the collection of the Qur'ān compilation took place under the [[Caliph]] [[Abu Bakr]], this task being led by [[Zayd ibn Thabit]] Al-Ansari. "The manuscript on which the Quran was collected, remained with [[Abu Bakr]] till [[Allah]] took him unto Him, and then with '[[Umar]] till Allah took him unto Him, and finally it remained with [[Hafsa bint Umar]] (Umar's daughter)."<ref> However, the Quran in a single manuscript form was only made during the reign of the Caliph Othman who ordered the production of several copies.[http://www.usc.edu/dept/MSA/fundamentals/hadithsunnah/bukhari/060.sbt.html#006.060.201 Sahih Bukhari, Volume 6, Book 60, Number 201]</ref>

| |

| | | | |

| − | ==Etymology and meaning==

| + | Islam holds that the Qur’an was revealed to Muhammad by the [[angel]] Jibrīl ([[Gabriel]]) over a period of approximately twenty-three years, beginning in 610 CE, when he was forty, and concluding in 632 CE, the year of his death.[2][6][7] Followers of Islam further believe that the Qur’an was written down by Muhammad's companions while he was alive, although the primary method of transmission was [[oral]]. Muslim [[tradition]] agrees that it was fixed in writing shortly after Muhammad's death by order of the caliphs [[Abu Bakr]] and [[Umar]][8], and that their orders began a [[process]] of formalization of the orally transmitted text that was completed under their successor Uthman with the standard edition known as the "Uthmanic recension."[9] The present form of the Qur’an is accepted by most scholars as the original version authored or dictated by Muhammad.[10] |

| − | <!-- [[Image:Holy quran cover.gif|right|thumb|150 px|Cover ornamentation with ''Al-Qur'ān Al-Karīm'' calligraphy]] -->

| |

| | | | |

| − | The original usage of the word "''{{Semxlit|ķur`ān}}''" is in the Qur'an itself, where it occurs about 70 times assuming various meanings. It is a verbal noun (''{{Semxlit|[[masdar|maṣdar]]}}'') of the [[Arabic]] verb "''{{Semxlit|ķara`a}}''" (Arabic: قرأ), meaning "he read" or "he recited," and represents the [[Syriac]] equivalent "''{{Semxlit|ķeryānā}}''" - which refers to "scripture reading" or "lesson." While most Western scholars consider the word to be derived from the Syriac, the majority of Muslim authorities hold the origin of the word is ''ķara`a'' itself.<ref name="EoI-Q">"Ķur'an, al-", ''Encyclopedia of Islam Online''.</ref> Among the earliest meanings of the word Qur'an is the "act of reciting", for example in a Qur'anic passage: "Ours is it to put it together and [Ours is] its ''ķur`ān''."<ref>Qur'an 75:17</ref> In other verses it refers to "an individual passage recited [by Muhammad]." In the large majority of contexts, usually with a [[definite article]] (''al-''), the word is referred to as the "revelation" (''tanzīl''), that which has been "sent down" at intervals.<ref>cf. Qur'an 20:2; 25:32</ref> Its [[liturgy|liturgical]] context is seen in a number of passages, for example:"So when ''al-ķur`ān'' is recited [by Muhammad], listen to it and keep silent."<ref>Qur'an 7:204</ref> The word may also assume the meaning of a codified scripture when mentioned with other scriptures such as the [[Tawrat|Torah]] and [[Injil|Gospel]].<ref>See:

| |

| − | *"Ķur'an, al-", ''Encyclopedia of Islam Online''.

| |

| − | *Qur'an 9:111</ref>

| |

| | | | |

| − | The term also has closely related [[synonym]]s which are employed throughout the Qur'an. Each of the synonyms possess their own distinct meaning, but their use may converge with that of ''ķur`ān'' in certain contexts. Such terms include "''{{Semxlit|kitāb}}''" ("book"); "''{{Semxlit|[[ayah|āyah]]}}''" ("sign"); and "''{{Semxlit|[[surah|sūrah]]}}''" ("scripture"). The latter two terms also denote units of revelation. Other related words are: "''{{Semxlit|dhikr}}''", meaning "remembrance," used to refer to the Qur'an in the sense of a reminder and warning; and "''{{Semxlit|hikma}}''", meaning "wisdom," sometimes referring to the revelation or part of it.<ref name="EoI-Q" /><ref>According to Welch in the Encyclopedia of Islam, the verses pertaining to the usage of the word ''hikma'' "should probably be interpreted in the light of IV, 105, where it is said that Muhammad is to judge ( tahkum) mankind on the basis of the Book sent down to him."</ref>

| + | ---- |

| | | | |

| − | == Format==

| + | <center>To read the '''''Qu'ran''''', follow [https://nordan.daynal.org/wiki/index.php?title=Category:The_Koran this link].</center> |

| − | {{main|Sura}}

| |

| − | [[Image:Fatiha.jpg|right|thumb|The first chapter of the Qur'an consisting of seven Ayat.]]

| |

| − | The Qur'an consists of 114 chapters of varying lengths, each known as a ''sura''. Each chapter possesses a title, usually a word mentioned within the chapter itself. In general, the longer chapters appear earlier in the Quran, while the shorter ones appear later. As such, the arrangement is not connected to the sequence of revelation. Each chapter commences with the ''bismillah ir rahman nir rahimm'',<ref>Arabic: {{lang|ar|بسم الله الرحمن الرحيم}}, transliterated as: ''{{ArabDIN|bismi-llāhi ar-raḥmāni ar-raḥīmi}}''.</ ref> an Arabic phrase meaning ("In the name of God, Most Gracious, Most Merciful"), with the exception of the ninth chapter. There are, however, still 114 occurrences of the basmala in the Qur'an, due to its presence in verse 27:30 as the opening of Solomon's letter to the Queen of Sheba. cf. ''[[Encyclopedia of Islam]],'' "Kur`an, al-"</ref><ref>See:

| |

| − | *"Kur`an, al-", ''Encyclopedia of Islam Online''

| |

| − | *Allen (2000) p. 53

| |

| − | </ref> | |

| | | | |

| − | === Literary structure===

| + | ---- |

| − | The Quran's message is conveyed through the use of a variety of literary structures and devices. In its original Arabic idiom, the individual components of the text — surahs and ayat — employ phonetic and thematic structures that assist the audience's efforts to recall the message of the text. There is consensus amongst Arab scholars to use the Quran as a standard by which other Arabic literature should be measured. Muslims point out (in accordance with the Quran itself) that the Quranic content and style is inimitable.<ref name = Issa> Issa Boullata, "Literary Structure of Qur'an," ''Encyclopedia of the Qur'an, vol.3 p.192, 204 </ref>

| |

| | | | |

| − | Richard Gottheil and Siegmund Fränkel in the [[Jewish Encyclopedia]] write that the oldest portions of the Qur'an reflect significant excitement in their language, through short and abrupt sentences and sudden transitions. The Qur'an nonetheless carefully maintains the rhymed form, like the [[oracle]]s. Some later portions also preserve this form but also in a style where the movement is calm and the style expository.<ref> [http://www.jewishencyclopedia.com/view.jsp?artid=369&letter=K&search=Quran]</ref>

| |

| | | | |

| − | [[Michael Sells]], citing the work of the critic [[Norman O. Brown]], acknowledges Brown's observation that the seeming "disorganization" of Qur'anic literary expression — its "scattered or fragmented mode of composition," in Sells's phrase — is in fact a literary device capable of delivering "profound effects — as if the intensity of the prophetic message were shattering the vehicle of human language in which it was being communicated."<ref> Michael Sells, ''Approaching the Qur'an'' (White Cloud Press, 1999), and Norman O. Brown, "The Apocalypse of Islam." ''Social Text'' 3:8 (1983-1984)</ref> Sells also addresses the much-discussed "repetitiveness" of the Qur'an, seeing this, too, as a literary device.

| + | Muslims regard the Qur’an as the main [[miracle]] of Muhammad, as [[proof]] of his [[prophet]]hood,[11] and as the culmination of a series of [[divine]] messages. These started, according to Islamic [[belief]], with the messages revealed to [[Adam]], regarded in Islam as the first prophet, and continued with the Suhuf Ibrahim (Sefer Yetzirah or Scrolls of Abraham),[12] the Tawrat ([[Torah]] or [[Pentateuch]]),[13][14] the Zabur (Tehillim or [[Book of Psalms]]),[15][16] and the Injeel (Christian [[Gospel]]).[17][18][19] The Qur'an assumes familiarity with major [[narratives]] recounted in [[Jewish]] and [[Christian]] [[scriptures]], summarizing some, dwelling at length on others, and, in some cases, presenting alternative accounts and interpretations of events.[20][21][22]. The Qur'an describes itself as book of guidance. It rarely offers detailed accounts of specific historical [[events]], and often emphasizes the moral significance of an event over its [[narrative]] sequence.[23] |

| − | | + | ==Etymology and meaning== |

| − | <blockquote>"The values presented in the very early Meccan revelations are repeated throughout the hymnic Suras. There is a sense of directness, of intimacy, as if the hearer were being asked repeatedly a simple question: what will be of value at the end of a human life?" <ref>Michael Sells, ''Approaching the Qur'an'' (White Cloud Press, 1999)</ref></blockquote>

| + | The word qur`ān appears in the Qur’an itself, where it occurs about 70 times assuming various [[meanings]]. It is a verbal noun (maṣdar) of the Arabic verb qara`a (Arabic: قرأ), meaning “he read” or “he recited”; the Syriac equivalent is qeryānā which refers to “scripture reading” or “lesson”. While most Western scholars consider the [[word]] to be derived from the Syriac, the majority of Muslim authorities hold the origin of the word is qara`a itself.[24] In any case, it had become an Arabic term by Muhammad's lifetime.[2] An important meaning of the word is the “act of reciting”, as reflected in an early Qur’anic passage: “It is for Us to collect it and to recite it (qur`ānatu)”.[25] |

| − | | |

| − | == Origin and development ==

| |

| − | {{POV-section}}

| |

| − | {{quotefarm|section}}

| |

| − | {{main|Origin and development of the Qur'an}}

| |

| − | {{Islam}}

| |

| − | [[Image:Uthman Koran-RZ.jpg|thumb|right|9th century quran]] | |

| − | According to Islam, Muhammad received the Qur'an as a series of revelations from God through the angel Gabriel (see {{Quran-usc-range|10|37|38}}), and is reported to have had mysterious seizures at the moments of inspiration. Welch, a scholar of Islamic studies, states in the [[Encyclopedia of Islam]] that he believes the graphic descriptions of Muhammad's condition at these moments may be regarded as genuine, since they are unlikely to have been invented by later Muslims. According to Welch, these seizures would have been seen as convincing evidence for the superhuman origin of Muhammad's inspirations by the people around him. Muhammad's enemies, however, accused him of being a man who was possessed, or of being a soothsayer or magician since his claimed experiences were similar to those made by those soothsayer figures well known in ancient Arabia. Additionally, Welch states that it remains uncertain whether these experiences occurred before or after Muhammad began to see himself as a prophet<ref> [[Encyclopedia of Islam]] online, Muhammad article </ref>

| |

| − | | |

| − | The Qur'ān speaks well of the relationship it has with former books (the [[Torah]] and the [[Gospel]]) and attributes their similarities to their unique origin and saying all of them have been revealed by one God (Allah).<ref>{{cite web|last=AL-BAQARA|title=Muslim texts||url=http://www.usc.edu/dept/MSA/quran/002.qmt.html#002.285 2:285|accessdate=2007-06-05}}</ref>

| |

| − | | |

| − | Based on Islam and nature of pre-islamic Arabia it is generally accepted Muhammad could neither read nor write. He was seen as intelligent and wise man who would simply recite what was revealed to him for his companions to write down and memorize.

| |

| − | However some scholars (mostly Western)- ([[Christoph Luxenberg]], [[Maxime Rodinson]], [[William Montgomery Watt]], etc.) - used to argue that the claim that Muhammad was not able to read and write at all is based on weak traditions and that, because of many details concerning Muhammad's biography and teachings, it is not convincing.

| |

| − | | |

| − | The Qur'an did not exist as a single volume between two covers at the time of the Prophet's death in [[632]]. According to [[Sahih al-Bukhari]], at the direction of the first Muslim caliph [[Abu Bakr]] this task fell to the scribe [[Zayd ibn Thabit]], who gathered the Quranic material "collecting it from parchments, scapula, leaf-stalks of date palms and from the memories of men who knew it by heart". (Bukhari {{Bukhari-usc|6|60|201}}).<ref>See also [http://ibnalhyderabadee.wordpress.com/2006/04/11/legacy-of-abu-bakr-compilation-of-the-quraan/] for an extended account incorporating further sources</ref>. Copies were made, and as Islam expanded beyond the Arabian peninsula into Persia, India, Russia, China, Turkey, and across North Africa, the third Caliph, [[Uthman ibn Affan]], in about [[650]] ordered a standardized version to be prepared to preserve the sanctity of the text and to establish a definitive spelling for all time. This remains the authoritative text of the Qur'an to this day.<ref>Mohamad K. Yusuff, [http://www.irfi.org/articles/articles_251_300/zayd_ibn_thabit_and_the_glorious.htm Zayd ibn Thabit and the Glorious Qur’an]</ref><ref>The Koran; A Very Short Introduction, Michael Cook. Oxford University Press, P.117 - P.124</ref>

| |

| − | | |

| − | Adherents to Islam hold that the wording of the Qur'anic text available today corresponds exactly to that revealed to [[Muhammad]] himself: as the words of God, said to be delivered to [[Muhammad]] through the angel [[Gabriel]]. The Qur'ān is not only considered by Muslims to be a guide but also as a sign of the prophethood of Muhammad and the truth of the religion. Muslims argue that it is not possible for a human to produce a book like the Qur'an, as the Qur'ān states: <blockquote> "And if ye are in doubt as to what We have revealed from time to time to Our servant, then produce a Sura like thereunto; and call your witnesses or helpers (If there are any) besides Allah, if your (doubts) are true. But if ye cannot- and of a surety ye cannot- then fear the Fire whose fuel is men and stones,- which is prepared for those who reject Faith. <ref>{{cite web|last=AL-BAQARA|url=http://www.usc.edu/dept/MSA/quran/002.qmt.html|title=USC-MSA Compendium of Muslim texts|accessdate=2007-06-07}}</ref></blockquote>

| |

| − | | |

| − | == Language==

| |

| − | {{quotefarm|section}}

| |

| − | The Qur'an is thought to be one of the first texts written in Arabic. It is written in the classical [[Arabic language|Arabic]] which is also the Arabic of [[Arabic poetry|pre-Islamic poetry]] including the ''[[Mu'allaqat]]'', or ''Suspended Odes''. Some scholars argue that the first Qur'an was not written in Arabic, but instead the spoken language of the time, namely a later Syro-Aramaic.

| |

| − | From ''The Foreign Vocabulary Of The Qur'an'', [[Arthur Jeffery]] 1938,

| |

| − | | |

| − | {{cquote|Soon after Muhammad's death in 632 CE, armies led by his followers burst out of Arabia and conquered the [[Near East]], [[Northern Africa]], [[Central Asia]], and parts of [[Europe]]. Arab rulers had millions of foreign subjects, with whom they had to communicate. Thus, the language rapidly changed in response to this new situation, losing complexities of case and obscure vocabulary. Several generations after the prophet's death, many words used in the Qur'ān had become opaque to ordinary sedentary Arabic-speakers, as Arabic had changed so much, so rapidly. The [[Bedouin]] speech changed at a considerably slower rate, however, and early Arabic lexicographers sought out Bedouin speech as well as pre-Islamic poetry to explain difficult words or elucidate points of grammar. Partly in response to the religious need to explain the Qur'an to Muslims who were not familiar with Qur'anic Arabic, [[Arabic grammar]] and lexicography soon became important sciences. The model for the Arabic [[literary language]] remains to this day the speech used in Qur'anic times, rather than the current spoken dialects. }}{{Facts|date=February 2007}}

| |

| − | | |

| − | ==Literary usage==

| |

| − | [[Image:IslamicGalleryBritishMuseum3.jpg|thumb|right|200px|11th Century North African Qur'an in the [[British Museum]]]]

| |

| − | In addition to and largely independent of the division into surahs, there are various ways of dividing the Qur'ān into parts of approximately equal length for convenience in reading, recitation and memorization. The Qur'ān is divided into thirty [[juz'|''ajza''']] (parts). The thirty parts can be used to work through the entire Qur'an in a week or a month. Some of these parts are known by names and these names are the first few words by which the Juz starts. A juz' is sometimes further divided into two [[hizb|''ahzab'']] (groups), and each hizb is in turn subdivided into four quarters. A different structure is provided by the ''[[ruku'at]]'' (sing. ''Raka'ah''), semantical units resembling paragraphs and comprising roughly ten ayat each. Some also divide the Qur'ān into seven [[manzil|''manazil'']] (stations).

| |

| − | | |

| − | === Recitation ===

| |

| − | The very word ''Qur'ān'' means "recitation", though there is little instruction in the Qur'an itself as to how it is to be recited. The main principle it does outline is: ''rattil il-Qur'ana tartilan'' ("repeat the recitation in a collected distinct way"). ''Tajwid'' is the term for techniques of recitation, and assessed in terms of how accessible the recitation is to those intent on concentrating on the words.<ref name = Sonn>{{Citation

| |

| − | | last = Sonn

| |

| − | | first = Tamara

| |

| − | | contribution = Art and the Qur'an

| |

| − | | year = 2006

| |

| − | | title = The Qur'an: an encyclopedia

| |

| − | | editor-last = Leaman

| |

| − | | editor-first = Oliver

| |

| − | | pages = 71-81

| |

| − | | place = Great Britain

| |

| − | | publisher = Routeledge

| |

| − | | id = }}

| |

| − | </ref>

| |

| − | | |

| − | To perform [[salat]] (prayer), a mandatory obligation in Islam, a Muslim is required to learn at least some [[sura]]s of the Qur'ān (typically starting with the first sura, [[al-Fatiha]], known as the "seven oft-repeated verses," and then moving on to the shorter ones at the end). Until one has learned al-Fatiha, a Muslim can only say phrases like "praise be to God" during the salat.

| |

| − | | |

| − | A person whose recital repertoire encompasses the whole Qur'ān is called a [[qari']] (قَارٍئ) or [[Hafiz (Quran)|hafiz]] (which translate as "reciter" or "protector," respectively). Muhammad is regarded as the first qari' since he was the first to recite it. [[Recitation]] (''[[tilawa]]'' تلاوة) of the Qur'ān is a fine art in the Muslim world.

| |

| − | | |

| − | ====Schools of recitation====

| |

| − | {{main|Qira'at}}

| |

| − | [[Image:Quran fragment 33,73-74.jpg|150px|thumb|right|Page of a 13th century Qur'an, showing [[Sura 33]]: 73]]

| |

| − | There are several schools of Qur'anic recitation, all of which are possible pronunciations of the Uthmanic [[rasm]]: Seven reliable, three permissible and (at least) four uncanonical - in 8 sub-traditions each - making for 80 recitation variants altogether<ref>Navid Kermani, Das ästhetische Erleben des Koran. Munich (1999)</ref>. For a recitation to be canonical it must conform to three conditions:

| |

| − | | |

| − | # It must match the rasm, letter for letter.

| |

| − | # It must conform with the syntactic rules of the [[Arabic language]].

| |

| − | # It must have a continuous [[isnad]] to [[Muhammad]] through ''[[tawatur]]'', meaning that it has to be related by a large group of people to another down the isnad chain.

| |

| − | | |

| − | These recitations differ in the vocalization (''tashkil'' تشكيل) of a few words, which in turn gives a complementary meaning to the word in question according to the rules of Arabic grammar. For example, the vocalization of a verb can change its active and passive voice. It can also change its [[Arabic grammar#Verb|stem]] formation, implying intensity for example. Vowels may be elongated or shortened, and glottal stops ([[hamza]]s) may be added or dropped, according to the respective rules of the particular recitation. For example, the name of archangel [[Gabriel]] is pronounced differently in different recitations: Jibrīl, Jabrīl, Jibra'īl, and Jibra'il. The name "Qur'ān" is pronounced without the glottal stop (as "Qurān") in one recitation, and prophet [[Abraham]]'s name is pronounced Ibrāhām in another.{{Fact|date=May 2007}}

| |

| − | <!-- Unsourced image removed: [[Image:Uthman moshaf.jpg|thumb|200px|left|Quran collected in Uthman era.]] -->

| |

| − | The more widely used narrations are those of [[Hafs]] (حفص عن عاصم), [[Warsh]] (ورش عن نافع), [[Qaloon]] (قالون عن نافع) and [[Al-Duri]] according to [[Abu `Amr]] (الدوري عن أبي عمرو). Muslims firmly believe that all canonical recitations were recited by the Muhammad himself, citing the respective [[isnad]] chain of narration, and accept them as valid for worshipping and as a reference for rules of [[Sharia]]. The uncanonical recitations are called "explanatory" for their role in giving a different perspective for a given verse or [[ayah]]. Today several dozen persons hold the title "Memorizer of the Ten Recitations." This is considered to be a great accomplishment among the followers of Islam.{{Fact|date=May 2007}}

| |

| − | | |

| − | The presence of these different recitations is attributed to many [[hadith]]. [[Malik Ibn Anas]] has reported:<ref>[[Malik Ibn Anas]], [[Muwatta]], vol. 1 (Egypt: Dar Ahya al-Turath, n.d.), 201, (no. 473).</ref>

| |

| − | :''Abd al-Rahman Ibn Abd al-Qari'' narrated: "[[Umar|Umar Ibn Khattab]] said before me: I heard ''Hisham Ibn Hakim Ibn Hizam'' reading Surah [[Al-Furqan|Furqan]] in a different way from the one I used to read it, and the [[Muhammad|Prophet]] (sws) himself had read out this surah to me. Consequently, as soon as I heard him, I wanted to get hold of him. However, I gave him respite until he had finished the prayer. Then I got hold of his cloak and dragged him to the Prophet (sws). I said to him: "I have heard this person [Hisham Ibn Hakim Ibn Hizam] reading Surah Furqan in a different way from the one you had read it out to me." The Prophet (sws) said: "Leave him alone [O 'Umar]." Then he said to Hisham: "Read [it]." [Umar said:] "He read it out in the same way as he had done before me." [At this,] the Prophet (sws) said: "It was revealed thus." Then the Prophet (sws) asked me to read it out. So I read it out. [At this], he said: "It was revealed thus; this Qur'ān has been revealed in Seven ''Ahruf''. You can read it in any of them you find easy from among them.

| |

| − | | |

| − | [[Suyuti]], a famous 15th century Islamic theologian, writes after interpreting above hadith in 40 different ways:<ref>[[Suyuti]], Tanwir al-Hawalik, 2nd ed. (Beirut: Dar al-Jayl, 1993), 199.</ref>

| |

| − | {{cquote|And to me the best opinion in this regard is that of the people who say that this Hadith is from among matters of ''mutashabihat'', the meaning of which cannot be understood.}}

| |

| − | | |

| − | Many reports contradict presence of variant readings:<ref name="jav">[[Javed Ahmad Ghamidi]]. [[Mizan]], ''[http://renaissance.com.pk/JanQur2y7.htm Principles of Understanding the Qu'ran]'', [[Al-Mawrid]]</ref>

| |

| − | *''Abu Abd al-Rahman al-Sulami'' reports, "the reading of [[Abu Bakr]], [[Umar]], [[Uthman]] and [[Zayd ibn Thabit]] and that of all the [[Muhajirun]] and the [[Ansar]] was the same. They would read the Qur'an according to the ''Qira'at al-'ammah''. This is the same reading which was read out twice by the Prophet (sws) to [[Gabriel]] in the year of his death. [[Zayd ibn Thabit]] was also present in this reading [called] the '''Ardah-i akhirah''. It was this very reading that he taught the Qur'an to people till his death".<ref>Zarkashi, al-Burhan fi Ulum al-Qur'ān, 2nd ed., vol. 1 (Beirut: Dar al-Fikr, 1980), 237.</ref>

| |

| − | *[[Ibn Sirin]] writes, "the reading on which the Qur'an was read out to the prophet in the year of his death is the same according to which people are reading the Qur'an today".<ref>[[Suyuti]], al-Itqan fi Ulum al-Qur'ān, 2nd ed., vol. 1 (Baydar: Manshurat al-Radi, 1343 AH), 177.</ref>

| |

| − | | |

| − | [[Javed Ahmad Ghamidi]] also purports that there is only one recitation of Qur'ān, which is called ''Qira'at of Hafs'' or in classical scholarship, it is called ''Qira'at al-'ammah''. The Qur'ān has also specified that it was revealed in the language of the prophet's tribe: the [[Quraysh]] ({{quran-usc|19|97}}, {{quran-usc|44|58}}).<ref name="jav"/> | |

| − | | |

| − | However, the identification of the recitation of Hafs as the ''Qira'at al-'ammah'' is somewhat problematic when that was the recitation of the people of Kufa in Iraq, and there is better reason to identify the recitation of the reciters of Madinah as the dominant recitation. The reciter of Madinah was Nafi' and Imam Malik remarked "The recitation of Nafi' is Sunnah." Moreover, the dialect of Arabic spoken by Quraysh and the Arabs of the Hijaz was known to have less use of the letter hamzah, as is the case in the recitation of Nafi', whereas in the Hafs recitation the hamzah is one of the very dominant features.{{Fact|date=May 2007}}

| |

| − | | |

| − | <blockquote>AZ [however] says that the people of El-Hijaz and Hudhayl, and the people of [[Makkah]] and [[Al-Madinah]], to not pronounce [[hamzah]] [at all]: and 'Isa Ibn-'Omar says, Tamim pronounce hamzah, and the people of Al-Hijaz, in cases of necessity, [in poetry,] do so.<ref>E. W. Lane, ''Arabic-English Lexicon''</ref></blockquote>

| |

| − | | |

| − | So the hamzah is of the dialect of the Najd whose people came to comprise the dominant Arabic element in Kufa giving some features of their dialect to their recitation, whereas the recitation of Nafi' and the people of Madinah maintained some features of the dialect of Hijaz and the Quraysh.{{Fact|date=May 2007}}

| |

| − | | |

| − | However, the discussion of the priority of one or the other recitation is unnecessary since it is a consensus of knowledgable people that all of the seven recitations of the Qur'an are acceptable and valid for recitation in the prayer. {{Fact|date=May 2007}}

| |

| − | | |

| − | Moreover, the so-called "un-canonical" recitations such as are narrated from some of the Companions and which do not conform to the Uthmani copy of the Qur'an are not legitimate for recitation in the prayer, but knowledge of them can legitimately be used in the tafsir of the Qur'an, not as a proof but as a valid argument for an explanation of an ayah.{{Fact|date=May 2007}}

| |

| − | | |

| − | === Writing and printing ===

| |

| − | [[Image:Large Koran.jpg|thumb|right|210px|Page from a Qur'ān ('Umar-i Aqta'). [[Iran]], present-day [[Afghanistan]], [[Timur]]id dynasty, circa 1400. Opaque [[watercolor]], ink and gold on paper Muqaqqaq script. 170 x 109cm (66 15/16 x 42 15/16in.)Historical Region: [[Uzbekistan]].]]

| |

| − | | |

| − | Most Muslims today use printed editions of the Qur'ān. There are many editions, large and small, elaborate or plain, expensive or inexpensive. Bilingual forms with the Arabic on one side and a gloss into a more familiar language on the other are very popular.

| |

| − | | |

| − | Qur'āns are produced in many different sizes, from extremely large Qur'āns for display purposes, to extremely small Qur'āns.

| |

| − | | |

| − | Qur'āns were first printed from carved wooden blocks, one block per page. There are existing specimen of pages and blocks dating from the 10th century AD. Mass-produced less expensive versions of the Qur'an were later produced by [[lithography]], a technique for printing illustrations. Qur'ans so printed could reproduce the fine calligraphy of hand-made versions.

| |

| − | | |

| − | The oldest surviving Qur'ān for which movable type was used was printed in [[Venice]] in 1537/1538. It seems to have been prepared for sale in the [[Ottoman empire]]. [[Catherine the Great]] of [[Russia]] sponsored a printing of the Qur'ān in 1787. This was followed by editions from [[Kazan]] (1828), [[Persia]] (1833) and [[Istanbul]] (1877). <ref>{{cite web|last=The Qur'an in Manuscript and Print|url=http://www.islamworld.net/UUQ/3.txt|title=THE QUR'ANIC SCRIPT|accessdate=2007-06-05}}</ref>

| |

| − | | |

| − | It is extremely difficult to render the full Qur'ān, with all the points, in computer code, such as [[Unicode]]. The [[Internet Sacred Text Archive]] makes computer files of the Qur'ān freely available both as images<ref>{{cite web|last=Article by A. Yusuf Ali|url=http://www.sacred-texts.com/isl/quran/index.htm|title=The Holy Qur'an|accessdate=2007-06-05}}</ref> and in a temporary Unicode version.<ref>{{cite web|last=Unicode Qur'an|url=http://www.sacred-texts.com/isl/uq/|title=Sacred-texts|accessdate=2007-06-05}}</ref> Various designers and software firms have attempted to develop computer fonts that can adequately render the Qur'ān.<ref>{{cite web|last=Mishafi Font|url=http://www.diwan.com/mishafi/main.htm|title=Award-winning calligraphic typeface|accessdate=2007-06-05}}</ref> | |

| − | | |

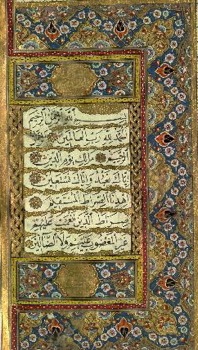

| − | Before printing was widely adopted, the Qur'ān was transmitted by copyists and calligraphers. Since Muslim tradition felt that directly portraying sacred figures and events might lead to idolatry, it was considered wrong to decorate the Qur'ān with pictures (as was often done for Christian texts, for example). Muslims instead lavished love and care upon the sacred text itself. Arabic is written in many scripts, some of which are both complex and beautiful. [[Arabic calligraphy]] is a highly honored art, much like [[Chinese calligraphy]]. Muslims also decorated their Qur'āns with abstract figures ([[arabesque]]s), colored inks, and gold leaf. Pages from some of these antique Qur'āns are displayed throughout this article.

| |

| − | | |

| − | Some Muslims believe that it is not only acceptable, but commendable to decorate everyday objects with Qur'anic verses, as daily reminders. Other Muslims feel that this is a misuse of Qur'anic verses, because those who handle these objects will not have cleansed themselves properly and may use them without respect.

| |

| − | | |

| − | === Translations ===

| |

| − | {{main|Translation of the Qur'an}}

| |

| − | Translation of the Quran has always been a problematic and difficult issue. Since Muslims revere the Qur'an as miraculous and inimitable (''i'jaz al-Qur'an''), they argue that the Qur'anic text can not be reproduced in another language or form. Furthermore, an Arabic word may have a [[Polysemy|range of meanings]] depending on the context, making an accurate translation even more difficult.<ref name = translation>{{Citation

| |

| − | | last = Fatani

| |

| − | | first = Afnan

| |

| − | | contribution = Translation and the Qur'an

| |

| − | | year = 2006

| |

| − | | title = The Qur'an: an encyclopedia

| |

| − | | editor-last = Leaman

| |

| − | | editor-first = Oliver

| |

| − | | pages = 657-669

| |

| − | | place = Great Britain

| |

| − | | publisher = Routeledge

| |

| − | | id = }}</ref>

| |

| − | | |

| − | Nevertheless, the Qur'ān has been [[Translation|translated]] into most African, Asian and European languages.<ref name = translation/> The first translator of the Qur'ān was [[Salman the Persian]], who translated [[Fatihah]] in Persian during the 7th century.<ref>An-Nawawi, Al-Majmu', (Cairo, Matbacat at-'Tadamun n.d.), 380. </ref> Islamic tradition holds that translations were made for Emperor Negus of Abyssinia and Byzantine Emperor [[Heraclius]], as both received letters by Muhammad containing verses from the Qur'an.<ref name = translation/>

| |

| − | | |

| − | In 1936, translations in 102 languages were known.<ref name = translation/>

| |

| − | | |

| − | [[Robert of Ketton]] was the first person to translate the Qur'ān into a Western language, [[Latin]], in 1143.<ref>{{cite book |coauthors= Bloom, Jonathan and Blair, Sheila | year=2002 | title=Islam: A Thousand Years of Faith and Power | publisher=Yale University Press | location=New Haven | pages=p. 42}}</ref>

| |

| − | [[Alexander Ross (writer)|Alexander Ross]] offered the first English version in 1649. In 1734, [[George Sale]] produced the first scholarly translation of the Qur'ān into English; another was produced by [[Richard Bell]] in 1937, and yet another by [[Arthur John Arberry]] in 1955. All these translators were non-Muslims. There have been numerous translations by Muslims; the most popular of these are the translations by [[Muhammad Muhsin Khan|Dr. Muhammad Muhsin Khan]] and Dr. Muhammad Taqi-ud-Din al Hilali, [[Maulana Muhammad Ali]], [[Abdullah Yusuf Ali]], [[Mohammed Habib Shakir|M. H. Shakir]], [[Muhammad Asad]], and [[Marmaduke Pickthall]][[Ahmed Raza Khan]].{{Fact|date=April 2007}}

| |

| − | | |

| − | The English translators have sometimes favored archaic English words and constructions over their more modern or conventional equivalents; thus, for example, two widely-read translators, A. Yusuf Ali and M. Marmaduke Pickthall, use the plural and singular "ye" and "thou" instead of the more common "[[you]]." Another common stylistic decision has been to refrain from translating "Allah" — in Arabic, literally, "The God" — into the common English word "God." These choices may differ in more recent translations.{{Fact|date=April 2007}}

| |

| − | | |

| − | === Interpretation ===

| |

| − | {{main article|Tafsir}}

| |

| − | The Qur'ān has sparked a huge body of commentary and explication, known as ''Tafsir''. This commentary is aimed at explaining the "meanings of the Qur'anic verses, clarifying their import and finding out their significance."<ref>[http://www.almizan.org/new/introduction.asp?TitleText=Introduction Preface of Al'-Mizan], reference is to [[Allameh Tabatabaei]]</ref>

| |

| − | | |

| − | Tafsir is one of the earliest academic activities of Muslims. According to the Qur'an, Muhammad was the first person who described the meanings of verses for early Muslims.<ref>[http://www.usc.edu/dept/MSA/quran/002.qmt.html 2:151]</ref> Other early exegetes included a few [[Companions of Muhammad]], like [[Ali ibn Abi Talib]], [[Abdullah ibn Abbas]], [[Abdullah ibn Umar]] and [[Ubayy ibn Kab]]. Exegesis in those days was confined to the explanation of literary aspects of the verse, the background of its revelation and, occasionally, interpretation of one verse with the help of the other. If the verse was about a historical event, then sometimes a few traditions ([[hadith]]) of Muhammad were narrated to make its meaning clear. <ref>[http://www.almizan.org/new/introduction.asp?TitleText=Introduction]</ref>

| |

| − | | |

| − | Because Qur'ān is spoken in the classical form of Arabic, many of the later converts to Islam, who happened to be mostly non-Arabs, did not always understand the Qur'ānic Arabic, they did not catch allusions that were clear to early Muslims fluent in Arabic and they were concerned with reconciling apparent conflict of themes in the Qur'an. Commentators erudite in Arabic explained the allusions, and perhaps most importantly, explained which Qur'anic verses had been revealed early in Muhammad's prophetic career, as being appropriate to the very earliest Muslim community, and which had been revealed later, canceling out or "[[naskh (exegesis)|abrogating]]" (''nāsikh'') the earlier text. Memories of the ''occasions of revelation ([[asbab al-nuzul|asbāb al-nuzūl]])'', the circumstances under which Muhammad had spoken as he did, were also collected, as they were believed to explain some apparent obscurities. Although the concept of abrogation does exist in the Qur'ān, Muslims differ in their interpretations of the word "Abrogation". Some believe that there are abrogations in the text of the Qur'ān and some insist that there are no contradictions or unclear passages to explain.{{Fact|date=April 2007}}

| |

| | | | |

| − | ==Relationship with other literature==

| + | In other verses, the word refers to “an [[individual]] passage recited [by [[Muhammad]]]”. In the large majority of [[contexts]], usually with a definite article (al-), the [[word]] is referred to as the “[[revelation]]” (wahy), that which has been “sent down” (tanzīl) at intervals.[26][27] Its [[liturgical]] context is seen in a number of passages, for example: "So when al-qur`ān is recited, listen to it and keep [[silent]]".[28] The word may also assume the meaning of a codified scripture when mentioned with other scriptures such as the Torah and Gospel.[29] |

| − | ===Torah and the Christian Bible===

| |

| − | {{main|Similarities between the Bible and the Qur'an}}

| |

| − | The Qur'ān retells stories of many of the people and events recounted in [[Judaism|Jewish]] and [[Christianity|Christian]] sacred books ([[Tanakh]], [[Bible]]) and devotional literature ([[Apocrypha]], [[Midrash]]), although it differs in many details. [[Adam and Eve|Adam]], [[Enoch (ancestor of Noah)|Enoch]], [[Noah]], [[Heber]], [[Shelah]], Abraham, [[Lot]], [[Ishmael]], [[Isaac]], [[Jacob]], [[Joseph (Hebrew Bible)|Joseph]], [[Job (Biblical figure)|Job]], [[Jethro]], [[David]], [[Solomon]], [[Elijah]], [[Elisha]], [[Jonah]], [[Aaron]], [[Moses]], Ezra, [[Zechariah (priest)|Zechariah]], [[Jesus]], and [[John the Baptist]] are mentioned in the Qur'an as prophets of God (see [[Prophets of Islam]]). Muslims believe the common elements or resemblances between the Bible and other Jewish and Christian writings and Islamic dispensations is due to the common divine source, and that the Christian or Jewish texts were authentic divine revelations given to prophets. According to the Qur'ān <blockquote>"It is He Who sent down to thee (step by step), in truth, the Book, confirming what went before it; and He sent down the Law (of Moses) and the Gospel (of Jesus) before this, as a guide to mankind, and He sent down the criterion (of judgment between right and wrong).{{Fact|date=March 2007}}[http://www.usc.edu/dept/MSA/quran/003.qmt.html 3:3] "</blockquote>

| |

| − | Muslims believe that those texts were neglected, corrupted ([[tahrif|''tahrif'']]) or altered in time by the Jews and Christians and have been replaced by God's final and perfect revelation, which is the Qur'ān.<ref> [[Bernard Lewis]], [[The Jews of Islam]] (1984). Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-00807-8. p.69 </ref> However, many Jews and Christians believe that the historical biblical archaeological record refutes this assertion, because the [[Dead Sea Scrolls]] (the [[Tanakh]] and other Jewish writings which predate the origin of the Qur'an) have been fully translated,<ref> The Dead Sea Scrolls Bible: The Oldest Known Bible Translated for the First Time into English (2002) HarperSanFrancisco. ISBN 0-06-060064-0 </ref> validating the authenticity of the Greek [[Septuagint]].<ref> http://www.septuagint.net </ref>

| |

| | | | |

| − | ===Influence of Christian apocrypha===

| + | The term also has closely related synonyms which are employed throughout the Qur’an. Each of the synonyms possess their own distinct meaning, but their use may converge with that of qur`ān in certain contexts. Such terms include kitāb (“[[book]]”); āyah (“[[sign]]”); and sūrah (“[[scripture]]”). The latter two terms also denote units of [[revelation]]. Other related words are: dhikr, meaning "remembrance," used to refer to the Qur’an in the sense of a reminder and warning; and hikma, meaning “wisdom”, sometimes referring to the revelation or part of it.[24][30] |

| − | The [[Diatessaron]], [[Protoevangelium of James]], [[Infancy Gospel of Thomas]], [[Gospel of Pseudo-Matthew]] and the [[Arabic Infancy Gospel]] are all invariably thought to have been sources that the author/authors drew on when creating the Qur'ān. The Diatessaron especially may have led to the misconception in the Koran that the Christian Gospel is one text.<ref>On pre-Islamic Christian strophic poetical tests in the Koran, Ibn Rawandi, ISBN 1-57392-945-X</ref>

| |

| | | | |

| − | === Arab writing===

| + | The Qur’an has many other names. Among those found in the text itself are al-furqan (“discernment” or “criterion”), al-huda (“"the guide”), dhikrallah (“the remembrance of God”), al-hikmah (“the wisdom”), and kalamallah (“the word of God”). Another term is al-kitāb (“the book”), though it is also used in the Arabic [[language]] for other scriptures, such as the Torah and the Gospels. The term mus'haf ("written work") is often used to refer to particular Qur'anic manuscripts but is also used in the Qur’an to identify earlier revealed books.[2] |

| − | After the Qur'an, and the general rise of Islam, the Arabic alphabet developed rapidly into a beautiful and complex form of art.<ref name = Calligraphy>{{Citation

| + | ==Text== |

| − | | last = Leaman

| + | The [[text]] of the Qur’an consists of 114 chapters of varying lengths, each known as a [[sura]]. Chapters are classed as Meccan or Medinan, depending on where the verses were revealed. Chapter titles are derived from a name or [[quality]] discussed in the text, or from the first letters or words of the sura. Muslims believe that Muhammad, on God's command, gave the chapters their names.[2] Generally, longer chapters appear earlier in the Qur’an, while the shorter ones appear later. The chapter arrangement is thus not connected to the sequence of [[revelation]]. Each sura except the ninth commences with the '''''Basmala'''''[31], an Arabic phrase meaning (“In the name of [[God]], Most [[Gracious]], Most [[Merciful]]”). There are, however, still 114 occurrences of the basmala in the Qur’an, due to its [[presence]] in verse 27:30 as the opening of Solomon's letter to the Queen of Sheba.[32] |

| − | | first = Oliver

| |

| − | | contribution = Cyberspace and the Quran

| |

| − | | year = 2006

| |

| − | | title = The Qur'an: an encyclopedia

| |

| − | | editor-last = Leaman

| |

| − | | editor-first = Oliver

| |

| − | | pages = 130-135

| |

| − | | place = Great Britain

| |

| − | | publisher = Routeledge

| |

| − | | id = }}

| |

| − | </ref>

| |

| | | | |

| − | Wadad Kadi, Professor of Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations at [[University of Chicago]] and Mustansir Mir, Professor of Islamic studies at [[Youngstown State University]] state that: <ref> Wadad Kadi and Mustansir Mir, ''Literature and the Qur'an'', [[Encyclopedia of the Qur'an]], vol. 3, pp. 213, 216 </ref>

| + | Each sura is formed from several ayat (verses), which originally means a sign or portent sent by [[God]]. The number of ayat differ from sura to sura. An individual ayah may be just a few letters or several lines. The ayat are unlike the highly refined poetry of the pre-Islamic Arabs in their [[content]] and distinctive rhymes and rhythms, being more akin to the prophetic utterances marked by inspired discontinuities found in the sacred scriptures of [[Judaism]] and [[Christianity]]. The actual number of ayat has been a controversial issue among Muslim scholars since Islam's inception, some recognizing 6,000, some 6,204, some 6,219, and some 6,236, although the words in all cases are the same. The most popular edition of the Qur’an, which is based on the Kufa school tradition, contains 6,236 ayat.[2] |

| | | | |

| − | <blockquote> Although Arabic, as a language and a literary tradition, was quite well developed by the time of Muhammad's prophetic activity, it was only after the emergence of Islam, with its founding scripture in Arabic, that the language reached its utmost capacity of expression, and the literature its highest point of complexity and sophistication. Indeed, it probably is no exaggeration to say that the Qur'an was one of the most conspicuous forces in the making of classical and post-classical Arabic literature. </blockquote>

| + | There is a crosscutting division into 30 parts, ajza, each containing two units called ahzab, each of which is divided into four parts (rub 'al-ahzab). The Qur’an is also divided into seven stations (manazil).[2] |

| − | <blockquote> The main areas in which the Qur'an exerted noticeable influence on Arabic literature are diction and themes; other areas are related to the literary aspects of the Qur'an particularly oaths (q.v.), metaphors, motifs, and symbols. As far as diction is concerned, one could say that qur'anic words, idioms, and expressions, especially "loaded" and formulaic phrases, appear in practically all genres of literature and in such abundance that it is simply impossible to compile a full record of them. For not only did the Qur'an create an entirely new linguistic corpus to express its message, it also endowed old, pre-Islamic words with new meanings and it is these meanings that took root in the language and subsequently in the literature...</blockquote>

| |

| | | | |

| − | ==Quranic Initials==

| + | The Qur’anic text seems to have no beginning, middle, or end, its [[nonlinear]] [[structure]] being akin to a web or net.[2] The textual arrangement is sometimes considered to have lack of continuity, absence of any chronological or thematic order, and presence of repetition.[33][34] |

| − | 14 different Arabic letters, form 14 different sets of “Quranic Initials” (the "[[Muqatta'at]]", such as A.L.M. of 2:1), and prefix 29 suras in the Quran. The meaning and interpretation of these initials is considered unknown to most Muslims. In 1974, an Egyptian biochemist named [[Rashad Khalifa]] claimed to have discovered a mathematical code based on the number 19<ref>Rashad Khalifa, ''Quran: Visual Presentation of the Miracle'', Islamic Productions International, 1982. ISBN 0-934894-30-2</ref>, which is mentioned in Sura 74:30<ref>[http://www.usc.edu/dept/MSA/quran/074.qmt.html#074.030 Qur'an, Chapter 74, Verse 30]</ref> of the Quran.

| |

| | | | |

| − | ==In culture==

| + | Fourteen different Arabic letters form 14 different sets of “Qur’anic Initials” (the "Muqatta'at", such as A.L.M. of 2:1) and prefix 29 suras in the Qur’an. The meaning and interpretation of these initials is considered unknown to most Muslims. In 1974, Egyptian biochemist Rashad Khalifa claimed to have discovered a mathematical code based on the number 19,[35] which is mentioned in Sura 74:30[36] of the Qur’an. |

| − | Most Muslims treat paper copies of the Qur'an with veneration, ritually washing before reading the Qur'an.<ref>Mahfouz (2006), p.35</ref> Worn out Qur'ans are not discarded as wastepaper, but are buried or burnt.<ref>{{cite web | url=http://www.salafyink.com/articles/What%20should%20be%20done%20with%20a%20torn%20Mushaf.pdf | title=How is a torn Mushaf (Qur'an) disposed of? | accessdate=2007-04-18 | author=The Permanent Committee of Research & Islamic Rulings

| + | ==Content== |

| − | Of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia.}}</ref> Many Muslims memorize at least some portion of the Qur'an in the original Arabic, usually at least the verses needed to perform the prayers. Those who have memorized the entire Qur'an earn the right to the title of ''[[Hafiz (Quran)|Hafiz]]''.<ref>Kugle (2006), p.47; Esposito (2000a), p.275</ref>

| + | The Qur'anic verses contain general exhortations regarding right and wrong and the nature of revelation. Historical events are related with a view to outlining general moral lessons. |

| | + | ===Literary structure=== |

| | + | The Qur’an's message is conveyed through the use of various literary [[structure]]s and devices. In the original Arabic, the chapters and verses employ phonetic and thematic structures that assist the [[audience]]'s efforts to recall the message of the [[text]]. There is consensus among Arab scholars to use the Qur’an as a standard by which other Arabic literature should be measured. Muslims assert (in accordance with the Qur’an itself) that the Qur’anic content and style is inimitable.[37] |

| | | | |

| − | Based on tradition and a literal interpretation of [[Al-Waqia|sura 56]]:77-79: ''"That this is indeed a Qur'ān Most Honourable, In a Book well-guarded, Which none shall touch but those who are clean."'', many scholars opine that a Muslim perform [[wudu]] (ablution or a ritual cleansing with water) before touching a copy of the Qur'ān, or ''[[mushaf]]''. This view has been contended by other scholars on the fact that, according to Arabic linguistic rules, this verse alludes to a fact and does not comprise an order. The literal translation thus reads as ''"That (this) is indeed a noble Qur'ān, In a Book kept hidden, Which none toucheth save the purified,"'' (translated by Mohamed Marmaduke Pickthall). It is suggested based on this translation that performing ablution is not required.

| + | Richard Gottheil and Siegmund Fränkel in the [[Jewish Encyclopedia]] write that the oldest portions of the Qur’an reflect significant excitement in their language, through short and abrupt sentences and sudden transitions. The Qur’an nonetheless carefully maintains the rhymed form, like the [[oracle]]s. Some later portions also preserve this form but also in a style where the movement is calm and the style expository.[38] |

| | | | |

| − | [[Qur'an desecration]] means insulting the Qur'ān by defiling or dismembering it. Muslims must always treat the book with reverence, and are forbidden, for instance, to pulp, recycle, or simply discard worn-out copies of the text. Respect for the written text of the Qur'ān is an important element of religious faith by many Muslims. They believe that intentionally insulting the Qur'ān is a form of [[blasphemy]]. In Islam, blasphemy is considered a sin. In the Qur'an, Allah says "He forgives all sins, except disbelieving in God (blasphemy)". In Islam if a person dies while in blasphemy, they will not enter heaven, except if said person repented before death. | + | [[Michael Sells]], citing the work of the critic [[Norman O. Brown]], acknowledges Brown's observation that the seeming "disorganization" of Qur’anic literary expression — its "scattered or fragmented mode of composition," in Sells's phrase — is in [[fact]] a literary device capable of delivering "profound effects — as if the intensity of the prophetic message were shattering the [[vehicle]] of human [[language]] in which it was being [[communicate]]d."[39][40] Sells also addresses the much-discussed "repetitiveness" of the Qur’an, seeing this, too, as a literary device. |

| | | | |

| − | ===Cyberspace=== | + | "The [[value]]s presented in the very early Meccan [[revelation]]s are repeated throughout the hymnic Suras. There is a sense of directness, of [[intimacy]], as if the hearer were being asked repeatedly a simple question: what will be of value at the end of a human life?" |

| − | The text of the Quran has become readily accessible over the internet, in Arabic as well as numerous translations in other languages. It can be downloaded and searched both word-by-word and with Boolean algebra. Photos of ancient manuscripts and illustrations of Quranic art can be witnessed. However, there are still limits to searching the Arabic text of the Quran.<ref name = rippin>{{Citation

| + | - Sells[39] |

| − | | last = Rippin

| + | ==Significance in Islam== |

| − | | first = Andrew

| + | Muslims believe the Qur’an to be the book of [[divine]] [[guidance]] and direction for mankind and consider the text in its original Arabic to be the literal word of [[God]],[41] revealed to [[Muhammad]] through the angel [[Gabriel]] over a period of twenty-three years[6][7] and view the Qur’an as God's final revelation to [[humanity]].[42][6] |

| − | | contribution = Cyberspace and the Quran

| |

| − | | year = 2006

| |

| − | | title = The Qur'an: an encyclopedia

| |

| − | | editor-last = Leaman

| |

| − | | editor-first = Oliver

| |

| − | | pages = 159-163

| |

| − | | place = Great Britain

| |

| − | | publisher = Routeledge

| |

| − | | id = }}

| |

| − | </ref>

| |

| | | | |

| − | ==Criticism==

| + | Wahy in Islamic and Qur’anic [[concept]] means the act of God addressing an individual, conveying a message for a greater number of recipients. The process by which the divine message comes to the [[heart]] of a messenger of God is tanzil (to send down) or nuzul (to come down). As the Qur'an says, "With the truth we (God) have sent it down and with the truth it has come down." It designates positive religion, the letter of the revelation dictated by the angel to the prophet. It means to cause this revelation to descend from the higher world. According to hadith, the verses were sent down in special circumstances known as asbab al-nuzul. However, in this view God himself is never the subject of coming down.[43] |

| − | {{main|Criticism of the Qur'an}}

| |

| | | | |

| − | The Qur'an's teachings on matters of war and peace have become topics of heated discussion in recent years. Some critics allege that some verses of the Qur'an in their historical and literary context sanction military action against unbelievers as a whole both during the lifetime of Muhammad and after.<ref>Robert Spencer. ''Onward Muslim Soldiers'', page 121.</ref><ref>Syed Kamran Mirza [http://www.mukto-mona.com/Articles/skm/islamic_terrorism.htm What is Islamic Terrorism and How could it be Defeated?]</ref> In response to this criticism, some Muslims argue that such verses of the Qur'an are taken out of context,<ref>Ali, Maulana Muhammad; The Religion of Islam (6th Edition), Ch V "Jihad" Page 413. Published by The Lahore Ahmadiyya Movement [http://www.aaiil.org/text/books/mali/religionislam/religionislammuhammadali.shtml]</ref><ref name="Boundries_Princeton"> Sohail H. Hashmi, David Miller, ''Boundaries and Justice: diverse ethical perspectives'', Princeton University Press, p.197 </ref><ref> Khaleel Muhammad, professor of religious studies at San Diego State University, states, regarding his discussion with the critic Robert Spencer, that "when I am told ... that Jihad only means war, or that I have to accept interpretations of the Quran that non-Muslims (with no good intentions or knowledge of Islam) seek to force upon me, I see a certain agendum developing: one that is based on hate, and I refuse to be part of such an intellectual crime." [http://www-rohan.sdsu.edu/~khaleel/]</ref> and claim that when the verses are read in context it clearly appears that the Qur'an prohibits aggression,<ref>Ali, Maulana Muhammad; The Religion of Islam (6th Edition), Ch V "Jihad" Page 414 "When shall war cease". Published by The Lahore Ahmadiyya Movement [http://www.aaiil.org/text/books/mali/religionislam/religionislammuhammadali.shtml]</ref><ref>Sadr-u-Din, Maulvi. "Quran and War", page 8. Published by The Muslim Book Society, Lahore, Pakistan. [http://www.aaiil.org/text/books/others/sadrdin/quranwar/quranwar.shtml]</ref><ref>[http://www.aaiil.org/uk/newsletters/2002/0302.shtml Article on Jihad] by Dr. G. W. Leitner (founder of The Oriental Institute, UK) published in Asiatic Quarterly Review, 1886. ("jihad, even when explained as a righteous effort of waging war in self defense against the grossest outrage on one's religion, is strictly limited..")</ref> and allows fighting only in self defense.<ref> [http://www.aaiil.org/text/articles/bash/quraniccommandmentswarjihad.shtml The Quranic Commandments Regarding War/Jihad] An English rendering of an Urdu article appearing in Basharat-e-Ahmadiyya Vol. I, p. 228-232, by Dr. Basharat Ahmad; published by the Lahore Ahmadiyya Movement for the Propagation of Islam</ref><ref>Ali, Maulana Muhammad; The Religion of Islam (6th Edition), Ch V "Jihad" Pages 411-413. Published by The Lahore Ahmadiyya Movement [http://www.aaiil.org/text/books/mali/religionislam/religionislammuhammadali.shtml]</ref> | + | The Qur'an frequently asserts in its text that it is divinely ordained, an assertion that Muslims believe. The Qur'an — often referring to its own textual nature and reflecting constantly on its divine origin — is the most meta-textual, self-referential religious text. The Qur'an refers to a written pre-text which records God's speech even before it was sent down.[44][45] |

| | + | “ And if ye are in doubt as to what We have revealed from time to time to Our servant, then produce a Sura like thereunto; and call your witnesses or helpers (If there are any) besides God, if your (doubts) are true. But if ye cannot — and of a surety ye cannot — then fear the Fire whose fuel is men and stones, which is prepared for those who reject Faith. ” |

| | + | —Qur'an 2:23–4 (Yusuf Ali) |

| | | | |

| − | Some critics reject the Muslim belief regarding the divine origin of the Qur'an<ref>[http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/08692a.htm Koran], by Gabriel Oussani, ''The Catholic Encyclopedia'', retrieved April 13, 2006</ref><ref>[[Patricia Crone]], [[Michael Cook]], and Gerd R. Puin as quoted in {{cite news | url=http://www.theatlantic.com/doc/199901/koran | publisher=The Atlantic Monthly | title=What Is the Koran? | author=Toby Lester |date=January 1999}}</ref><ref>Jewish Encyclpoedia: comp. also xvi. 70 </ref>, and base their argument on the problems that they claim to exist in the Qur'ān, both textually and morally.<ref>''The Encyclopedia of Religion'', By Mircea Eliade. Volum 12 pg. 165-6, pub. 1987 ISBN 0-02-909700-2</ref><ref>Robert Spencer. ''Onward Muslim Soldiers,''</ref>

| + | The issue of whether the Qur'an is eternal or created was one of the crucial controversies among early Muslim theologians. Mu'tazilis believe it is created while the most widespread varieties of Muslim theologians consider the Qur'an to be eternal and uncreated. Sufi philosophers view the question as artificial or wrongly framed.[46] |

| | | | |

| − | Some critics have also commented on the arrangement of the Qur'anic text with accusations of lack of continuity, absence of any chronological or thematic order, and presence of repetition<ref> Samuel Pepys: "One feels it difficult to see how any mortal ever could consider this Koran as a Book written in Heaven, too good for the Earth; as a well-written book, or indeed as a book at all; and not a bewildered rhapsody; written, so far as writing goes, as badly as almost any book ever was!" http://maxwellinstitute.byu.edu/display.php?table=review&id=21 </ref><ref>"The final process of collection and codification of the Qur'an text was guided by one over-arching principle: God's words must not in any way be distorted or sullied by human intervention. For this reason, no serious attempt, apparently, was made to edit the numerous revelations, organize them into thematic units, or present them in chronological order.... This has given rise in the past to a great deal of criticism by European and American scholars of Islam, who find the Qur'an disorganized, repetitive, and very difficult to read." ''Approaches to the Asian Classics,'' Irene Blomm, William Theodore De Bary, Columbia University Press,1990, p. 65</ref>. Others have praised the Quran's style as a book of divine guidance<ref>''The New Approach to the Study of the Quran,'' Dr. hasanuddin Ahmed, 2004, page 13, Goodword books,

| + | Muslims maintain the present wording of the Qur'anic text corresponds exactly to that revealed to Muhammad himself: as the words of God, said to be delivered to Muhammad through the angel Gabriel. Muslims consider the Qur'an to be a guide, a sign of the prophethood of Muhammad and the truth of the religion. They argue it is not possible for a human to produce a book like the Qur'an, as the Qur'an itself maintains. |

| − | Quote:"Its style, in accordance with its contents and aim, is stern, grand, forcible - ever and anon truly sublime...It soon attracts, astounds, and in the end enforces our reverence"</ref>, and its eloquence has been described as near perfect by Dr. [[Francis Steingass]] due to the Quran's "ability to transform savage tribes into civilized nations."<ref> The "Dictionary of Islam" by Thomas Patrick Hughes, p 528

| |

| − | Quote: "its eloquence was perfect, simply because it created a civilized nation out of savage tribes, and shot a fresh woof into the old warp of history."

| |

| − | | |

| − | == See also ==

| |

| − | * [[Ayat]]

| |

| − | * [[Esoteric interpretation of the Qur'an]]

| |

| − | * [[Hafiz (Quran)|Hafiz]]

| |

| − | * [[Islam]]

| |

| − | * [[Origin and development of the Qur'an]]

| |

| − | * [[Persons related to Qur'anic verses]]

| |

| − | * [[Qur'an and miracles]]

| |

| − | * [[Qur'an alone]]

| |

| − | * [[Qur'an and Sunnah]]

| |

| − | * [[Qur'anic literalism]]

| |

| − | * [[Qur'an reading]]

| |

| − | * [[Sura]]

| |

| − | * [[Tafsir]]

| |

| − | * [[Women in Quran]]

| |

| − | * There are also articles on each of the [[sura]]s, or chapters, of the Qur'ān. Click on a chapter number to view the article.

| |

| − | {{Sura|||}}

| |

| − | | |

| − | ==Notes==

| |

| − | <div class="references-small" style="-moz-column-count:2; column-count:2;">

| |

| − | <references />

| |

| − | </div>

| |

| | | | |

| | + | Therefore an Islamic philosopher introduces a prophetology to explain how the divine word passes into human expression. This leads to a kind of [[esoteric]] [[hermeneutics]] which seeks to comprehend the position of the [[prophet]] by meditating on the modality of his relationship not with his own time, but with the eternal source from which his message emanates. This view contrasts with historical critique of western scholars who attempt to understand the prophet through his circumstances, [[education]] and type of [[genius]].[47] |

| | + | ==Miracle== |

| | + | Islamic scholars believe the Qur’an to be miraculous by its very [[nature]] in being a revealed text and that similar texts cannot be written by [[human]] endeavor. Its miraculous nature is claimed to be evidenced by its literary style, suggested similarities between Qur’anic verses and scientific [[fact]]s discovered much later, and various prophecies. The Qur’an itself challenges those who deny its claimed divine origin to produce a text like it. [Qur'an 17:88][Qur'an 2:23][Qur'an 10:38].[48][49][50] These claims originate directly from Islamic [[belief]] in its revealed nature, and are widely disputed by non-Muslim scholars of Islamic [[history]].[51][https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Quran] |

| | ==References== | | ==References== |

| − | *{{cite book | last=Allen | first=Roger | title=An Introduction to Arabic literature | year=2000 | publisher=Cambridge University Press | id=ISBN 0521776570}}

| + | # [https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/en/5/5b/Quran.ogg pronounced qurˈʔaːn] |

| − | *{{cite book | last=Esposito | first=John | authorlink=John Esposito | coauthors=Yvonne Yazbeck Haddad | title=Muslims on the Americanization Path? | year=2000 | publisher=Oxford University Press | id=ISBN 0-19-513526-1}}

| + | Arabic pronunciation (help·info) |

| − | *{{cite book | last=Esposito | first=John | authorlink=John Esposito | year=2002 | title=What Everyone Needs to Know about Islam | publisher=Oxford University Press | id=ISBN 0-19-515713-3}}

| + | #Nasr, Seyyed Hossein (2007). "Qur’an". Encyclopedia Britannica Online. Retrieved 2007-11-04. |

| − | *{{cite book | last=Kugle | first=Scott Alan | title=Rebel Between Spirit And Law: Ahmad Zarruq, Sainthood, And Authority in Islam | publisher=Indiana University Press| year=2006 | id=ISBN 0253347114}}

| + | # Qur'an 2:23–24 |

| − | *{{cite book | last=Mahfouz | first=Tarek | title=Speak Arabic Instantly | publisher= Lulu Press, Inc. | year=2006 | id=ISBN 1847289002}}

| + | # Qur'an 33:40 |

| − | *{{cite book | last=Molloy | first=Michael | title=Experiencing the World's Religions | publisher=McGraw-Hill | edition=4th | year=2006 | id=ISBN 978-0073535647}}

| + | # Watton, Victor, (1993), A student's approach to world religions:Islam, Hodder & Stoughton, pg 1. ISBN 0-340-58795-4 |

| − | | + | #Living Religions: An Encyclopaedia of the World's Faiths, Mary Pat Fisher, 1997, page 338, I.B. Tauris Publishers. |

| − | ===Further reading===

| + | #Qur'an 17:106 |

| − | {{Wikisourcerename|The Holy Qur'an}}

| + | # Sahih al-Bukhari 6:60:201 |

| − | ;Translations

| + | # The Koran: A Very Short Introduction Michael Cook, Oxford University Press, 2000. |

| − | * [http://quranexplorer.com/ Interactive Authenticated Quran Translations & Recitations in English] Also available in Urdu, Indonesian, Malay, Turkish, French and Dutch

| + | # See: William Montgomery Watt in The Cambridge History of Islam, p.32 Richard Bell, William Montgomery Watt, Introduction to the Qur’an, p.51 F. E. Peters (1991), pp.3–5: “Few have failed to be convinced that … the Qur’an is … the words of Muhammad, perhaps even dictated by him after their recitation.” |

| − | * [http://www.mysticletters.com/ Read Quran Online] - Specialized site for easy reading of Quran online with English & Arabic views, page themes, and ability to customize font styling.

| + | # Peters (2003), pp.12 and 13 |

| − | * [http://www.guidedways.com/list.php Quran in English, Urdu, French, Spanish and German] - English versions include translations by Dr. M. Mohsin Khan, Yusuf Ali and Pickthal.

| + | # Qur'an 87:18–19 |

| − | * [http://www.ahadees.com/quran.html Quran - The Knazul Iman] - English Version translated from the Original by Imam [[Ahmed Raza Khan]], a [[Sunni]] Islamic Scholar.

| + | # Qur'an 3:3 |

| − | * [http://www.islamibayanaat.com/EnglishMarefulQuran.htm English Translation and Explanation of Quran, Maariful Quran] by Mufti Taqi Usmani, Prof. Shamim (Tafsir by Mufti Maulana Muhammad Shafi Usmani RA)

| + | # Qur'an 5:44 |

| − | * [http://www.GlobalQuran.com GlobalQuran.com] over 30 different languages of translation and search in all of them at once, also be able add Quran on your site/blog.

| + | # Qur'an 4:163 |

| − | * [http://www.usc.edu/dept/MSA/quran/ The Qur'an at USC-MSA] - three translations (Yusuf Ali, Shakir, and Pickthal). Also, Abul Ala Maududi's chapter introductions to the Qur'an.

| + | # Qur'an 17:55 |

| − | * [http://www.sacred-texts.com/isl/index.htm#quran The Qur'an] at the [[Internet Sacred Text Archive]]

| + | # Qur'an 5:46 |

| − | * [http://www.islamawakened.com/Quran/ Islam Awakened] - ayat-by-ayat transliteration and parallel translations from eleven prominent translators.

| + | # Qur'an 5:110 |

| − | * [http://islam.thetruecall.com/modules.php?name=Quran Quran Translation and Phonetic Search] Translations in English, French, German, Japanese, Russian and Portuguese with English and Phonetic Search

| + | # Qur'an 57:27 |

| − | * [http://www.islamicity.com/QuranSearch/ IslamiCity Qur'an search]

| + | # Qur'an 3:84 |

| − | * [http://www.hti.umich.edu/k/koran/ Qur'ān] Search or browse the English Shakir translation

| + | # Qur'an 4:136 |

| − | * [http://www.qran.org/q-chrono.htm Qur'ān Verses in Chronological Order]

| + | # “The Qur’an assumes the reader to be familiar with the traditions of the ancestors since the age of the Patriarchs, not necessarily in the version of the ‘Children of Israel’ as described in the Bible but also in the version of the ‘Children of Ismail’ as it was alive orally, though interspersed with polytheist elements, at the time of Muhammad. The term Jahiliya (ignorance) used for the pre-Islamic time does not mean that the Arabs were not familiar with their traditional roots but that their knowledge of ethical and spiritual values had been lost.” Exegesis of Bible and Qur’an, H. Krausen. https://www.geocities.com/athens/thebes/8206/hkrausen/exegesis.htm |

| − | * [http://www.textinmotion.com/ Text In Motion], concordance searchable by root or by grammatical form. | + | # * Nasr (2003), p.42 |

| − | | + | #“Ķur'an, al-”, Encyclopedia of Islam Online. |

| − | Older commentary

| + | # Template:Quran-Yusuf Ali |

| − | * al-Tabari, Muhammad ibn Jarir -- ''Jami' al-bayān `an ta'wil al-Qur'ān'', Cairo [[1955]]-[[1969|69]], transl. J. Cooper (ed.), ''The Commentary on the Qur'an'', Oxford University Press, 1987. ISBN 0-19-920142-0

| + | # Qur'an 20:2 cf. |

| − | * Tafsir Ibn-Kathir, Hafiz Imad al-din Abu al-Fida Ismail ibn Kathir al-Damishqi al-Shafi'i - (died 774 Hijrah (Islamic Calendar))

| + | # Qur'an 25:32 cf. |

| − | * Tafsir Al-Qurtubi (Al-Jami'li-Ahkam), Abu Abdullah Muhammad ibn Ahmad Abi Bakr ibn Farah al-Qurtubi - (died 671 Hijrah (Islamic Calendar))

| + | # Qur'an 7:204 |

| − | | + | # See “Ķur'an, al-”, Encyclopedia of Islam Online and [Qur'an 9:111] |

| − | ;Older scholarship

| + | # According to Welch in the Encyclopedia of Islam, the verses pertaining to the usage of the word hikma should probably be interpreted in the light of IV, 105, where it is said that “Muhammad is to judge (tahkum) mankind on the basis of the Book sent down to him.” |

| − | * [[Theodor Nöldeke|Nöldeke, Theodor]] -- ''Geschichte des Qorâns'', Göttingen, 1860.

| + | # Arabic: بسم الله الرحمن الرحيم, transliterated as: bismi-llāhi ar-raḥmāni ar-raḥīmi. |

| − | | + | # See: “Kur`an, al-”, Encyclopaedia of Islam Online |

| − | ;Recent scholarship

| + | Allen (2000) p. 53 |

| − | * [[Al-Azami]], M. M. -- ''The History of the Qur'anic Text from Revelation to Compilation'', UK Islamic Academy: Leicester 2003.

| + | # Samuel Pepys: "One feels it difficult to see how any mortal ever could consider this Koran as a Book written in Heaven, too good for the Earth; as a well-written book, or indeed as a book at all; and not a bewildered rhapsody; written, so far as writing goes, as badly as almost any book ever was!" https://maxwellinstitute.byu.edu/display.php?table=review&id=21 |

| − | * [[Gunter Luling]] A challenge to Islam for reformation: the rediscovery and reliable reconstruction of a comprehensive pre-Islamic Christian hymnal hidden in the Koran under earliest Islamic reinterpretations. New Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publishers 2003. (580 Seiten, lieferbar per Seepost). ISBN 81-2081952-7

| + | # "The final process of collection and codification of the Qur’an text was guided by one over-arching principle: God's words must not in any way be distorted or sullied by human intervention. For this reason, no serious attempt, apparently, was made to edit the numerous revelations, organize them into thematic units, or present them in chronological order.... This has given rise in the past to a great deal of criticism by European and American scholars of Islam, who find the Qur’an disorganized, repetitive, and very difficult to read." Approaches to the Asian Classics, Irene Blomm, William Theodore De Bary, Columbia University Press,1990, p. 65 |

| − | * [[Christoph Luxenberg|Luxenberg, Christoph]] (2004) -- [[The Syro-Aramaic Reading Of The Qur'an|The Syro-Aramaic Reading Of The Koran: a contribution to the decoding of the language of the Qur'an]], Berlin, Verlag Hans Schiler, 1 May 2007 ISBN 3-89930-088-2

| + | # Rashad Khalifa, Qur’an: Visual Presentation of the Miracle, Islamic Productions International, 1982. ISBN 0-934894-30-2 |

| − | * [[Jane Damen McAuliffe|McAuliffe, Jane Damen]] -- ''Quranic Christians : An Analysis of Classical and Modern Exegesis'', Cambridge University Press, 1991. ISBN 0-521-36470-1

| + | # Qur'an 74:30 Prophecies Made in the Qur’an that Have Already Come True] |

| − | * McAuliffe, Jane Damen (ed.) -- ''Encyclopaedia of the Qur'an'', Brill, 2002-2004.

| + | # Issa Boullata, "Literary Structure of Qur’an," Encyclopedia of the Qur’an, vol.3 p.192, 204 |

| − | * [[Gerd R. Puin|Puin, Gerd R.]] -- "Observations on Early Qur'an Manuscripts in Sana'a," in ''The Qur'an as Text'', ed. Stefan Wild, , E.J. Brill 1996, pp. 107-111 (as reprinted in ''What the Koran Really Says'', ed. Ibn Warraq, Prometheus Books, 2002)

| + | # JewishEncyclopedia.com - KÖRNER, MOSES B. ELIEZER: |

| − | * [[Fazlur Rahman|Rahman, Fazlur]] -- ''Major Themes in the Qur'an'', Bibliotheca Islamica, 1989. ISBN 0-88297-046-1

| + | #Michael Sells, Approaching the Qur’an (White Cloud Press, 1999) |

| − | *[[Louay M. Safi]] -- [http://qthemes.wordpress.com/ Quranic Themes]

| + | # Norman O. Brown, "The Apocalypse of Islam." Social Text 3:8 (1983-1984) |

| − | * [[Neal Robinson|Robinson, Neal]], ''Discovering the Qur'an'', Georgetown University Press, 2002. ISBN 1-58901-024-8

| + | # Qur'an 2:23–4 |

| − | * [[Michael Sells|Sells, Michael]], -- ''Approaching the Qur'an: The Early Revelations,'' White Cloud Press, Book & CD edition (November 15, 1999). ISBN 1-883991-26-9

| + | # Watton, Victor, (1993), A student's approach to world religions:Islam, Hodder & Stoughton, pg 1. ISBN 0-340-58795-4 |